THE VICTORIANS AT CHRISTMAS

5-minute read

Explore how the Victorians popularised and celebrated Christmas with this selection of artworks and Victorian Christmas cards.

QUEEN VICTORIA'S CHRISTMAS TREE

At the dawn of the 19th century, Christmas was hardly celebrated. By the end of the century, Christmas had become the biggest annual celebration in the British calendar.

As well as having an impact on society as a whole, Victorian advancements in technology, industry and infrastructure made Christmas an occasion that many more British people could enjoy. Victorian life was full of colour and not the smog-filled dark and dreary time we often imagine.

Two of the most popular seasonal traditions also emerged in the Victorian era, the Christmas tree and the Christmas card.

The royal Christmas tree being admired by Queen Victoria, Prince Albert and their children, December 1848. Image Wikimedia © Public domain

The Germans are credited with first bringing evergreens into their homes and decorating them, a tradition which made its way to the United States in the 1830s. But it wasn't until the German-born Prince Albert introduced the tree to his new wife, England's Queen Victoria, that the tradition took off.

The couple were sketched in front of a Christmas tree in 1848, and when the Illustrated London News published the drawing, royal fever did its work.

The popularity of decorated Christmas trees grew quickly, and with it came a market for tree ornaments in bright colours and reflective materials that would shimmer and glitter in the candlelight.

Queen Victoria’s Christmas tree at Windsor Castle in 1850, oil on panel, William Corden copy of the James Robert watercolour © Royal Collection

Mechanisation and the improved printing processes meant decorations could be mass-produced and advertised to eager buyers. The first advertisements for tree ornaments appeared in 1853.

Victorians would often combine their sparkly bought decorations with candles and homemade edible treats, tied to the branches with ribbon.

The Christmas tree was originally a festive tradition stemming from the Roman Saturnalia. These festivities, which marked the winter solstice in December, celebrated Saturn, the Roman god of time and agriculture. During the winter, branches served as a reminder of spring - and became the root of our Christmas tree.

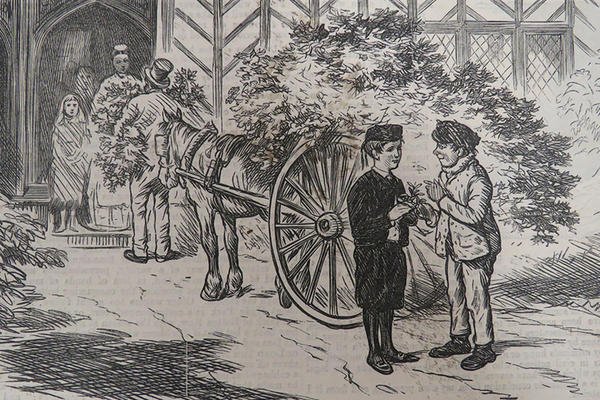

'Buying the Mistletoe' by Charles Green, 1862, illustration for London Society magazine © Ashmolean Museum

The Victorians also continued another Saturnalia tradition of kissing under the mistletoe at Christmas. This had become popular in the 1700s, as it was thought to symbolise fertility and romance. According to Victorian custom, it was said that a maiden who refused the offer of a kiss under the mistletoe would jinx her chances of getting married the following year.

SIR HENRY COLE'S CHRISTMAS CARD, THE FIRST

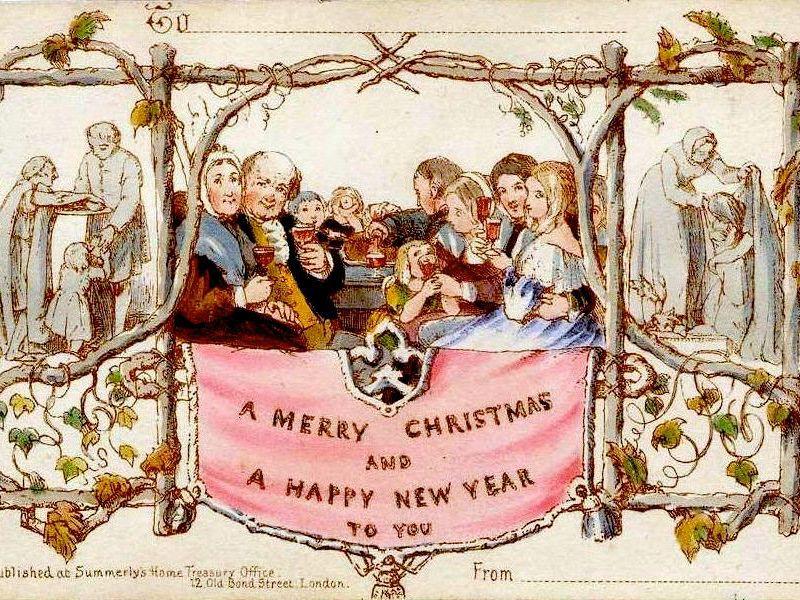

It was Sir Henry Cole, the first director of the South Kensington Museum (later the V&A), who introduced the idea of the Christmas card in 1843.

Finding he was too busy to send his customary Christmas letters to all his friends and acquaintances, Cole commissioned the artist John Callcott Horsley to design a festive-themed card for him to send instead. He had 1,000 printed, and those he didn't use himself were sold to the public.

Christmas card, designed by John Callcott Horsley for Henry Cole in 1843 © Public domain

The card design, in true Victorian style, depicted the two sides of Christmas. A central image which portrayed Henry’s family happiness with a plenitude of food and drink was flanked by two scenes showing the less fortunate poor and needy being helped with gifts of food and clothing.

The card was of a similar size to a postcard and carried the message ‘A Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year to You’.

Later in the century, improvements to the chromolithographic printing process made buying and sending Christmas cards affordable for everyone.

Fringed Victorian Christmas cards. Examples of the Victorian chromolithograph printing process using new mass-produced synthetic colours © Private collection

VICTORIAN CHRISTMAS TRADITIONS DEPICTED IN OUR COLLECTION

Christmas pudding

Boar's head feast

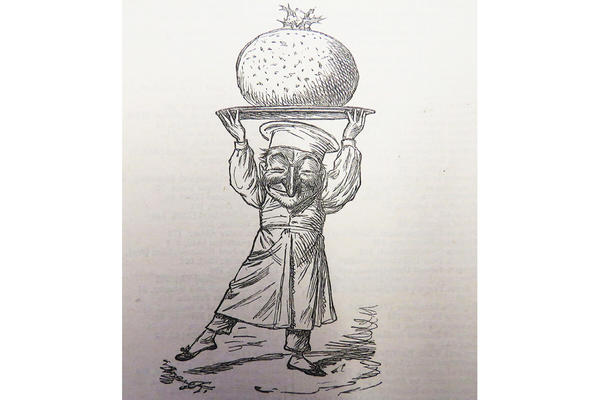

Mr Punch and the Christmas pudding

Robin and mistletoe

Mistletoe

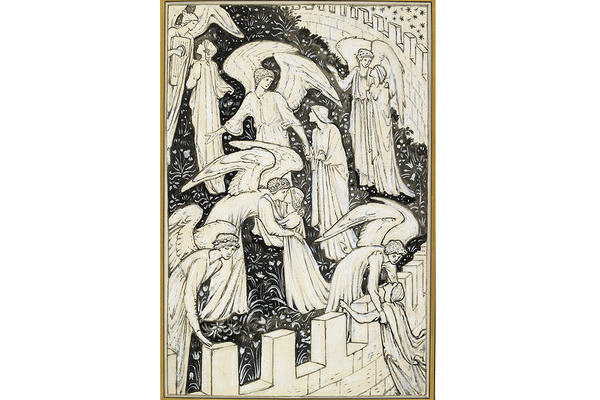

Choir of 'angels'

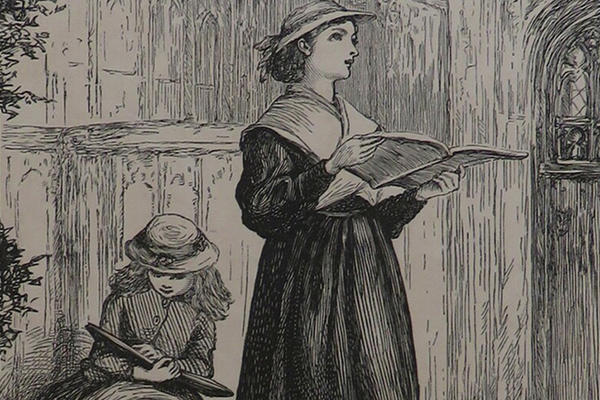

Christmas choir

Christmas angels

Christmas ballad

Walks in the snow

CHRISTMAS FOR ORDINARY VICTORIANS

One of the most significant cultural shifts within the Victorian period was the introduction of the holiday season, which occurred as a result of the Industrial Revolution. The increase in wealth and improvements in infrastructure allowed more factory workers to take Christmas Day and Boxing Day off, and celebrate the holiday with their families.

The term Boxing Day originated when the less fortunate opened their boxes of gifts from the wealthier classes. It is still commonly used today in Britain and Canada to celebrate the day after Christmas.

'They dined off a twopenny loaf and a pennyworth of milk', by George John Pinwell, 1866, depicts a scene from 'A Crust on Christmas Day' in The Quiver, a Victorian evangelical magazine © Ashmolean Museum

At the beginning of the Victorian era, the children of the rich received handmade toys, which were quite labour-intensive to make and expensive. The children of the poor received stockings filled with fruit and nuts, a tradition we still have today.

With the onset of the Industrial Revolution and mass production, factories were able to produce toys more rapidly and much less expensively, so they became more accessible to all. These toys often featured the newly mass-produced synthetic dyes in their bright colours which, as we now know today, included toxic elements such as lead and arsenic!

Conservative though they were, the Victorians believed Christmas should be celebrated (although excessive drinking and frolicking were frowned upon). It was they who established the tradition of making the Christmas pudding on Stir Up Sunday, the fifth Sunday before Christmas.

The Poor Actress's Christmas Dinner, by Robert Braithwaite Martineau, c.1860. A remarkable example of mid-Victorian pathos painted in sharp detail, but unfinished © Ashmolean Museum

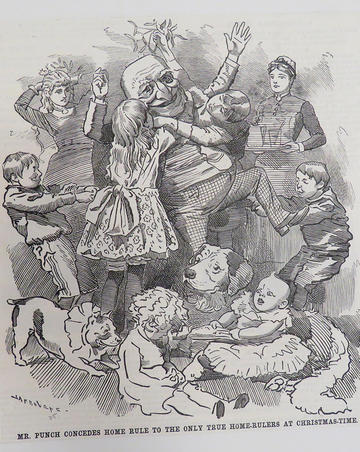

The plum pudding, which appeared on greetings cards and in satirical cartoons of the time, would come to epitomise Christmas. Rich or poor, every Victorian would expect a pudding as the finale to their festive meal.

Charles Dickens has certainly helped plant Christmas in our minds as a very Victorian custom. In A Christmas Carol, Charles Dickens wrote:

'In half a minute Mrs Cratchit entered – flushed, but smiling proudly – with the pudding, like a speckled cannon ball, so hard and firm, blazing in half a half a quartern of ignited brandy, and bedight with Christmas Holly stuck into the top. Oh, what a wonderful pudding!'

On that note, we wish you all a happy festive season and relaxing break.

'Mr Punch concedes Home Rule to the only true home-rulers at Christmas-time', by Edward Linley Sambourne, 1885 © Ashmolean