DINING WITH THE MINOANS

What did the Minoan people who lived at Knossos thousands of years ago eat and drink?

4-minute read

By Andrew Shapland

Sir Arthur Evans Curator of Bronze Age and Classical Greece

Some of the objects on display in the Ashmolean's Labyrinth exhibition provide clues of the food and farming practices of the ancient Minoan civilisation: cups for drinking wine, a painting of an olive tree, and even food remains from the time the settlement was first inhabited 9,000 years ago.

When we were asked by the team at Heston Blumenthal’s restaurant Dinner to help create a new menu based on the exhibition, we enlisted the help of experts from Oxford University’s School of Archaeology to give us some of the answers based on their research at the Knossos archaeological site.

Uncover more with the exhibition's curator, Andrew Shapland.

FIRST STORAGE VESSELS FOUND AT KNOSSOS

Pithos storage jar (right) excavated by Minos Kalokairinos (pictured) in the Labyrinth exhibition © Ashmolean Museum

Archaeologists now think that the palace burned down in around 1350 BCE, by which time it was about 600 years old.

From the time of its foundation, there is evidence that it was a place for collecting and storing agricultural goods, as well as throwing parties – hence the cups.

Middle Minoan ‘eggshell ware’ ceramic cups, 1800–1750 BCE, Knossos Palace: Royal Pottery Stores. AN1896-1908.AE.947 (left) & AN1938.561 (right) © Ashmolean Museum

Catastrophic events which destroy buildings are often good news for archaeologists, since they can help to preserve things.

IMPORTANCE OF OLIVE OIL

The importance of olives for the economy was reinforced by the discovery of a fresco showing an olive tree gently swaying in the breeze.

Restored fresco showing olive tree, 1700–1450 BCE, painted plaster, 75 × 70 cm, Knossos, Heraklion Museum T36 B. © Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports, General Directorate of Antiquities and Cultural Heritage, Heraklion Archaeological Museum

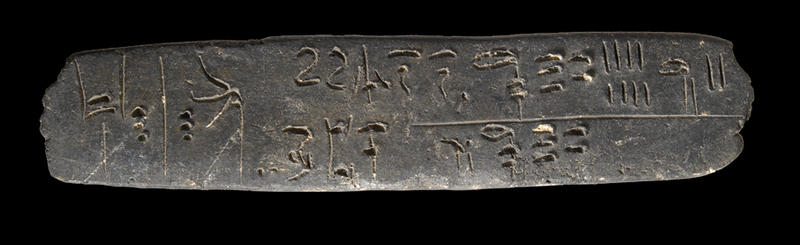

Clay tablets found at Knossos were temporary records of commodities, including olive oil. They were written in a script called 'Linear B', which was used for an early form of Greek. These clay tablets were accidentally baked by the fire which destroyed the palace, providing evidence for the economy of the time.

Olive oil would have been used for a variety of things, including cooking, but was also the base for the manufacture of perfume. It was boiled with wine and various plants including coriander to infuse it with scent. A Linear B tablet from another site on mainland Greece provided the recipe for perfume that the team at Dinner repurposed for their dessert.

Olive Oil 'Perfume' dessert (inspired by c.1300-1200 BCE perfume). Maury wine, fig, pear & goats milk ice cream © Dinner by Heston Blumenthal

WOOL AND BULLS

At Knossos a large number of tablets detailed sheep; 100,000 in total. These animals were kept for their wool, but older animals were removed from the flock for slaughter.

Leaf-shaped Linear B tablet counting sheep, c. 1350 BCE. AN1938.850 © Ashmolean Museum

The wool was then dyed using organic pigments, purple from sea snails and orange from saffron crocuses, before it was woven into elaborate textiles by women workers, also detailed on the tablets. The purple-bearing snails are still eaten on Crete but are harder to procure in London.

The Dinner menu included a shellfish dish garnished with saffron. Certainly, seafood was consumed at Knossos, despite the sea being a few kilometres away.

There are some records of animal butchery too, particularly pigs and cattle. Among the extraordinary finds made by Arthur Evans at Knossos was a stone vessel in the shape of a bull’s head. The Ashmolean’s plaster replica is on display in the Labyrinth exhibition. Real animal heads were probably put on display during feasts.

Replica bull’s head rhyton, 20th century in painted plaster, AN1896-1908.AE.2400 © Ashmolean Museum

This remarkably lifelike rhyton (a pouring vessel) would have been filled with wine, which would have come out through a hole at the mouth.

It would have been quite a performance, and we gave the team at Dinner a 3D scan of the replica to play with. They filled their 3D print with dry ice and used it to diffuse a specially made scent. It was in keeping with the theatrical nature of this vessel.

BONES AND GRAINS... EARLIEST EVIDENCE OF AGRICULTURE IN EUROPE

When Arthur Evans excavated Knossos in the early 20th century, animal and plant remains were not routinely kept by archaeologists.

The archaeological teams who worked at Knossos from the 1950s onwards did start to keep things like bones and seeds, realising their potential for revealing information about ancient diets. When some of these bones were restudied by Dr Valasia Isaakidou, she found that deer had been brought to Crete, most probably to be kept in an enclosure near Knossos and hunted.

Looking at the cut marks on other bones even revealed evidence for the method of preparation, cut against the grain of the meat. These were older animals too, eaten after being used for other agricultural activities. Dinner served a similar cut of beef as their main course, as well as a venison starter.

The excavations at Knossos In the 1950s and 1960s also dug down through to the bottom of the hill on which the palace sits. It is an artificial mound, built up by thousands of years of occupation.

Domestic animal bones (cow, pig, goat, sheep), 7000–6500 BCE, Knossos © Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports, General Directorate of Antiquities and Cultural Heritage, Ephorate of Antiquities of Heraklion

The lowest levels were carbon dated to around 7000 BCE and the finds there included bones from the four main domesticated animal species (cattle, sheep, goat and pig) and burnt wheat grains (as with the clay tablets, burning helped preserve them). Bones were sometimes recycled to make eating implements - the exhibition incudes a bone spoon, perhaps the oldest ever found in Europe!

Carbonised wheat grains, 6700–6500 BCE, Knossos © Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports / General Directorate of Antiquities and Cultural Heritage, Ephorate of Antiquities of Heraklion

These are still the earliest evidence for the arrival of agriculture in Europe, brought by a group of settlers from somewhere in the Eastern Mediterranean. They can be seen in the Labyrinth exhibition and are currently being restudied as part of an Oxford University research project AGRICURB.

THE ORIGINAL MEDITERRANEAN DIET

Another research project which fed into the exhibition, and menu, was the dig at Gypsades, a few hundred metres from the palace at Knossos.

This involved a team from the University of Oxford led by Prof. Amy Bogaard who were excavating a Bronze Age house.

They focused on recovering evidence for the food remains in this building, showing that a variety of different types of plants, including pulses, were being stored there. The Dinner menu included a take on a Cretan split pea puree, fava.

This evidence is a reminder that most people at Knossos ate a largely plant-based diet with meat as an occasional luxury, which has become known as the traditional Mediterranean diet.

Cretan bowl and spoon display from the Labyrinth exhibition 6700–6500 BCE, Knossos © Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports / General Directorate of Antiquities and Cultural Heritage, Ephorate of Antiquities of Heraklion

Though most people don’t eat at a Michelin starred restaurant every day, Dinner’s Labyrinth menu has brought to life some of the research that Oxford University is undertaking to understand a typical prehistoric diet.

Short Rib of Beef on the Labyrinth menu at Dinner by Heston © Dinner by Heston Blumenthal

I would like to thank Deiniol Pritchard and his colleagues from Dinner, as well as Amy Bogaard, Valasia Isaakidou and Rena Veropoulidou for a fruitful collaboration.

Dinner's Labyrinth menu was available until the end of April 2023 at Dinner by Heston Blumenthal at Mandarin Oriental Hyde Park, London.